![]()

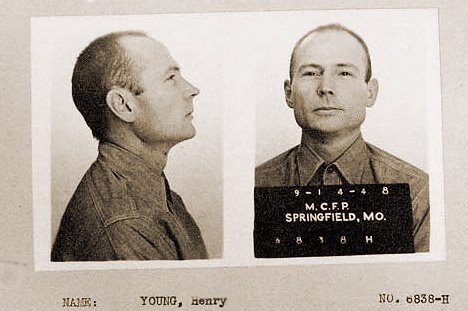

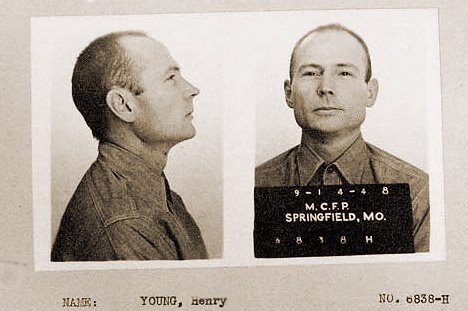

The doctors at the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners (formerly known as the Center for Defective Delinquents), Springfield, Missouri had all the records on Henri Young that had ever been filed. They pored over his conduct reports, read his medical records, and conducted some tests of their own. He'd been sent from Alcatraz after guards had observed him assuming strange postures and not eating his meals. Alcatraz's new chief surgeon, Dr. Yocum, injected Henri with sodium amytal. He snapped out of his catatonia with each dose, but lapsed back as the drug wore off. On September 3, 1948, Warden Swope received the order to transfer Young to Springfield.(2)

The Springfield classification committee was left with a question: was Young truly mentally ill or was he malingering? Committee members read and reread Young's correspondence to his family. Here he talked about being qualified as an "expert" in Abnormal Psychology at a friend's trial (which actually did not happen because the judge and district attorney would not allow it). Springfield psychiatrists also heard from Alcatraz that he had read many books on psychology. They suspected he might be studying them to mimic disorders which required hospitalization.

Upon arrival at Springfield, staff found him "confused, apathetic, flattened, dull". He sat quietly in his cell, spoke to no one unless spoken to, and then only seemed able to respond to simple questions. He ate well and kept himself and his cell immaculate. "[H]e gave the impression that he did not know where he was or where he had come from." Once they caught him talking to an old friend from the Rock about life there.

They conducted numerous interviews and psychiatric tests. By the end of these, they were uncertain whether Henri was truly disturbed or faking it. For one thing, they observed, he maintained a fixed pattern of responses when answering questions, as if he were imitating a ten or twelve year old boy. They also noted

a peculiar Ganserish quality to his replies. For instance when asked where he is he answers with much hesitation, "Spring---, Spring---, Spring---" and after only much deep thought he brings out the "field". He spells some simple words of three letters, but spells boy as boi, girl as gerl, desk as dak, pencil as pensil, and chair as car. 2 plus 2 is 4, and 3 plus 3 is six, but 9 plus 7 is 15, and 2 x 3 is 5 and 2 x 4 is 6. He says that San Francisco is in the West, but cannot say where, that New York is in the East but he does not know exactly where, similarly with London. When asked who the first president was he says "Not George Washington". After the detection of this syndrome of approximate answer which could lead one to strongly suspect malingery the inmate was given a large battery of psychological tests....(3)

The tests proved inconclusive. Some of his responses, particularly on the Rohrscach, seemed genuinely psychotic. His thematic apperception test, in which he was asked to tell stories about some pictures he was shown, suggested to the doctors who evaluated the results that he was smarter than his IQ tests showed. In a word association test, Young gave high quality associations but blocked and hesitated when given words like Alcatraz, Rock, Leavenworth, the names of family members, and Franklin.

Dr. Robert B. Neu had his doubts about Young and deferred his diagnosis, just in case Young was truly malingering, but also felt that Young's files and behavior evidenced "a very severe character disorder".(4) Neu's doubts disappeared as he continued to observe Henri. Young lapsed back into his catatonia. Springfile doctors snapped him out of his stupor by injecting him with sodium pentathol. The loquacious paranoic who emerged in these interviews reveled in a classic Protestant conspiracy theory:

He says that all of psychiatric text books and knowledge is false due to the fact that all psychiatrists are merely Jesuits in plain clothes, that they have been indoctrinated by the followers of St. Ignacious (Whom Young knows to have been a woman) as part of a grand scale attempt to subjugate the human race to their own purposes. He says that when he went to trial at San Francisco, the leader of the Jesuit underground came to him and offered him a job as a leader of their movement in return for which he would be given a chaste Nun for his own sexual purposes. The inmate states that he rejected these offerings because he himself was a leader of a much greater movement which is bent upon pointing out the fallaciousness of all psychiatry and of exposing the Jesuits as plotters against the human race. He says that he continues to lead the movement even from his cell and says in a mystical fashion even though he is locked in a cell there are three members with him.(5)

His catatonia, Neu concluded, could be described as reactive. Henri assumed odd postures, but he didn't hold to them with the passive stubbornness of the classic catatonic. Nor did he soil himself or display periods of hyperactivity. Against his own paranoia, Henri erected a bulwark of silence. Though Springfield doctors doubted it would do anything more than disintegrate Henri's catatonic defense, making him a very conscious paranoid, they asked his family's permission to perform electro-shock therapy. They refused.(6)

What was Young's problem? Henri's life history suggests many causes for his disturbance. After his father and mother divorced and he came down with polio, Henri dropped out of school. He loved his mother very deeply, ignoring her coldness towards him in some situation and her love of material goods. He idealized her. Perhaps she did or said something that caused him to feel betrayed. Disagreements with Ammie Payne, the imperfect man who his mother married when Henry turned 17, led him to leave his stable job as a telegraph clerk and his studies in telegraphy to pursue a life of the road, two years later.

This life ended when he recklessly stole a flashlight from a man he described as a "degenerate". He put his trust in an attorney who promised him that he would only be sent up to Deer Lodge for 30 days and then betrayed him by asking for and getting a fifteen month sentence. Or so Henri told it. Perhaps the truth is that Henri held hope that a gentle justice would prevail and when things did not go as he wished, the Law became another of his fallen idols.

Henri admitted that he'd devoted himself to learning the criminal arts at Deer Lodge. When he came out in 1933, he put his skills to practice in the state of Washington where he was arrested for burglary and sent to Walla Walla. Here he met new friends who became part of a gang he formed after his 1934 release. During this crime spree, Henri kidnapped a cab driver, stole a car, killed a man during a bakery robbery attempt, and then attempted to knock over the Lind National Bank. Henri's first murder cannot be described as premeditated: the man tried to knock the gun out of his hand. There was a struggle. The panicked Young shot a single bullet into the baker's chest and fled the scene, not bothering the witnesses who gaped at the pool of blood filling the low spots of the floor. For eight years, he and his compatriots kept this secret, even after being captured for the Lind bank robbery.

During his prison time, he'd visited the Hole often and probably also spent time in Alcatraz's dungeons, located in the maze-like foundations of the Old Citadel beneath the Cell House. In this place of legend, Henri froze and fumbled in the dark. It intensified his feelings of enmity towards McCain and the Alcatraz staff. Fellow convict James Groves, another maddened graduate of the dungeons, testified that Young had been beaten by Associate E.J. Miller. Possibly the guards only sought to subdue Young as it suggests in the report. In the minds of two disturbed prisoners, their efforts to carry the kicking and screaming Young to the Hole became an all out assault. Or maybe Miller did kick Young repeatedly in the head (though he didn't lose all his teeth like Groves said). The event remained in Young's memory, embroidered by his unhappy mind into an attempt to maim or kill him.

He created other fictions. He claimed that, during the knifing of McCain, he blacked out and did not remember either executing the attack or preparing to do so. McCain had been his partner and, presumably, a trusted friend. After the breakout failed, Young's friendship with McCain deteriorated when the latter took a job delivering meals in the Isolation area. In Henri's eyes, this must have been treason and McCain became what Sol Abrams described to the jury as "the embodiment of evil" in Young's eyes. He either suffered or imagined homosexual advances from McCain. (He would get very angry if anyone suggested that he was a homosexual.) Being in isolation and being severely punished pushed him to the brink of paranoia: McCain, he decided, was out to get him.

And so Young executed his former friend.

Immediately after his trial, Young told a reporter how he, McCain, and the others had shattered the tool-proof bars in D-Block. This made him a security risk to the Warden and a snitch to the other convicts who'd succeeded in keeping the secret from the staff for more than two years. He became the subject of two codes of law. When he started learning his Catholic catechism, Henri again aroused the suspicion of the Warden, who thought he was pulling another fast one, and the ire of his fellow convicts who believed that he was selling them out by confessing to his crimes. Henri's purge of his soul led to a conviction for murder in the State of Washington and a letting of his blood by Rufus Franklin, one of the last of the original Rock-bound Barker gang. Young expected Johnston to protect him, but the Warden, who still retained bitterness about the bad press he'd received from Young's accusations of brutality in the 1941 trial, chose to punish him with Franklin and Franklin's accomplice Willis Coulter for "feuding". Henri invoked the law, invented endless ways to author writs to secure alleviation of his pain, and discovered his "protectors" unwilling to give him relief.

There is evidence that Young engaged in other reckless behavior. He was a frequent visitor to the hospital, where Dr. Ritchey alternatively prescribed amphetamines for his depressions and bromides when he was too anxious. Young may also have received additional helpings of amphetamines through the jailhouse drug network, but there is no evidence for this. At his 1941 trial, it was revealed that he sometimes sipped a noxious tipple made of gasoline and milk. Henri Young undoubtably took other chances like these when he could.

When depression drove him to suicide, Young saw the danger and sought to fight for relief from it via religious redemption. Religious zealotry became his defense against the despair arising from his mistreatment by Alcatraz officials and his fellow prisoners. He became narcisstic, believing that the trials he suffered were a process by which God was absolving him of his sins and preparing him for great work. Henri saw himself as an instrument of the Divine Will against those who blasphemed against the Spirit. He also styled himself as an expert on Abnormal Psychology (which, in a sense he was) and enjoyed making a mockery of the Alcatraz staff when brought to San Francisco to appear in a trial or when being interviewed by the Associate Warden about one of his recent challenges to the Warden's authority. It was his mission to bring the high down or so he imagined.

From the start of his stay in the Federal penitentiary system, Young had been called "emotionally unstable". No one doubted that he required psychiatric supervision. But in the prison psychotherapy practiced on Alcatraz under the guidance of Warden Johnston, there were only two kinds of people with the symptoms Henri exhibited: those with organic causes and those who were acting that way to try to get something. Warden Johnston was a strict moralist who believed that the restrictions and bruiseless punishments he imposed were nothing more than what was called for by the inmate's behavior. If an inmate broke in the dungeons or the hole, there was either something wrong before or the fellow was trying to get sympathy. Repeatedly, Johnston stuck Young in the second category.

Personality disorders (or "character" disorders as they were called in the late forties) emerge as a reaction to stress. Sufferers defend themselves against cruelty or betrayal by adopting a certain set of behaviors. Henri Young had felt abandoned by his parents, who divorced when he was fourteen, and by the justice system which punished him too harshly for the theft of a flashlight. When one of his idols betrayed him, he turned utterly against that person. He became impulsive, attacking the guards verbally, fellow prisoners physically. He didn't consider the danger before starting to free himself from D-Block. He incited riots, inviting subduals which may have turned into beatings by the guards. He mocked the staff, calling them fools from the lowest to the highest level of authority. He may have been right in his assessments and he may have been telling the truth about what was done to him, but it is also true that he persisted in drawing these attacks to himself.

Pain was Young's way of life. He drank suspect tipple. He tore up his cell so that it was unliveable. He tried to kill himself. But though Dr. Ritchey recommended his transfer, if for no other reason than to get him out of the way in the event of a prison uprising, Johnston would not allow this. Like others with the effrontery to challenge Johnston's control of the institution such as Whitey Phillips(7), Henri Young was chained to Alcatraz as long as Johnston remained Warden. Religion was the way that Young sought to fill the emptiness of his life. That, however, depended on him being able to do good works, like alleviating the suffering of his fellows in prisons, including the guards. Young had few if any successes in this area. Though he was able to control his temper, he never could get Johnston to understand that he acted out of pain.

Treatment for personality disorders requires the establishment of trust between the therapist and the patient.(8) Alcatraz was hardly the place where Young could receive sympathy from medical professionals. Dr. Ritchey and Warden Johnston sought to find purposes behind Young's every symptom. His impulsive behaviors, his sudden and intense anger, his unstable mood, his love-hate relationships, his feelings of emptiness, and his paranoia all showed themselves before he was 30 years of age. In the beginning, Henri acted out of self-defense or revenge against those who had hurt him. But as time passed, he lost control of his emotions. The way of life that he had chosen for himself became his master. Young, who had no organic dysfunction, worked his way into being genuinely mad. Alcatraz did not reform Young: it was a partner in the making of a psychotic.

No amount of pleading would move Johnston to allow Young's release and Director Bennett would not act against the Rock's Warden. Only after Warden Swope took over (and Warden Swope, who had his personal enemies in Robert Stroud and Alvin Karpis, was rumored to hate Johnston, too), did Alcatraz medical officials and the classification committee succeed in acting to place Young where he could be properly diagnosed and receive the relief he needed.

Henri kept to himself at Springfield. He kept himself and his room clean, worked as a hospital orderly, and spent a lot of time listening to the radio and reading. Philosophy was a favorite topic and he could rattle off a list of philosophers he'd read. He responded flatly to questions put to him and sometimes spoke of people in an odd fashion which led his psychiatrists to consider certification. "His is poor," he would say. "and a criminal. Him is rich and a criminal, it doesn't make any sense." The remarks reflected Henri's frustration and confusion with his situation. A man turned to crime because he was desparate. Why would a rich man want to break the law? He remained, however, hopeful of the future, when he planned to work in a trucking firm as a shipping clerk. In the meantime, he planned to "just...coast along as the other people fight".(9)

In 1957, Young was transferred to the State of Washington to serve out his life sentence for the baker's murder. He was released in the 1970s and disappeared. His name became remembered when the movie Murder in the First was released, but the innocent Henry of the film was not the Henri who'd shot the baker and robbed the Lind National Bank. The film's makers changed the details of the story of his life, even causing him to conveniently die after the trial was over, victorious over the evil associate warden Miller (who they piously saw never worked again in a prison) and the absentee landlord, James A. Johnston. All these characters were fictions, fictions woven out of the legends of Alcatraz and out of a scriptwriter's idea about what should have happened. Henry got a happy ending and a victory Henri didn't get in life. Ironically, in telling a story about someone else who was named Henry Young, the film's producers, director, writers, actors, and crew succeeded in attaining one of Warden Johnston's constant intentions for all those who came to the Rock: they made Henri Young a forgotten man.

![]()

![]()

[The End]